This page highlights my work designing Competency-Based Education (CBE) learning experiences, along with other professional projects.

Page last updated: August 22nd, 2025 (Fixed typo)

Competency-Based Education

CBE for Student Learning

In 2002, the UF College of Pharmacy expanded its PharmD program with a blended learning model. Lectures recorded at the Gainesville campus were streamed to distant campuses within hours, marking a major shift in how instruction was delivered.

To prepare students for the program’s heavy reliance on technology, I designed a “Computer and Technology Orientation” course. Students practiced essential skills such as navigating the LMS, submitting assignments, posting to discussions, and completing practice quizzes and surveys. Over time, the orientation expanded to include requirements for webcams and “iDevices” (iPhone, iPod Touch, or iPad). Students learned to record video, install apps, and join Elluminate web conferences.

The course had to be completed before the semester began, with guidance and opportunities for resubmission provided until requirements were met. In effect, we were applying the principles of Competency-Based Education—ensuring students could demonstrate the technology skills needed to succeed before they ever entered the classroom. Later, I adapted and facilitated a similar course at the UF College of Veterinary Medicine.

CBE for Professional Development

When developing new online instructor training at Santa Fe College, our goal was to make each module both practical and immediately applicable. Every assignment aligned with the module’s outcome while producing a resource faculty could use directly in their teaching.

For example, in the Universal Design module, participants created an accessible course page on a topic of their choice. Their pages included text descriptions, sub-headers, a relevant image with alternative text, and a captioned or transcribed video. Participants rated this module as the most useful because it demonstrated how to integrate accessibility into real teaching materials within an evidence-based pedagogical framework.

Later at SF College, I addressed the text-heavy nature of online courses by creating and leading the Educational Media Certificate program. Each module guided faculty through the creation or curation of instructional media and resulted in a usable teaching product. CBE principles were embedded throughout—faculty could revise and resubmit work until outcomes were met.

Perhaps my most valuable contribution was incorporating an in-person media studio tour. Participants enjoyed watching me flub a short recording (which normalized failure), and many practiced reading from a teleprompter. Beyond the training itself, the tour introduced faculty to our supportive media studio staff. Participant survey feedback revealed this was the highlight of the program.

How *NOT* to Engage in CBE

Competency-Based Education measures mastery of skills and knowledge, not simply behaviors like punctuality or timely submissions. Early in my teaching career, I often lost sight of this distinction.

With the best of intentions, I enforced strict course policies: late assignments were penalized heavily, quizzes could not be made up, and six absences meant automatic failure. While these rules promoted time management, they also meant that students who had, in fact, mastered the course outcomes could still fail due to scheduling conflicts, family responsibilities, or health issues.

I later realized that these policies placed unnecessary barriers between students and evidence of their learning. At times, even my attempts at flexibility created problems. For example, allowing students to drop their lowest score unintentionally encouraged some to skip the group assignment—leaving me without evidence of their collaboration skills.

Over time, I revised my courses to focus less on compliance and more on meaningful evidence of learning. This shift brought my teaching more in line with the principles of CBE: evaluating students on what they can do, rather than on whether they perfectly adhered to logistical rules.

Innovative Work

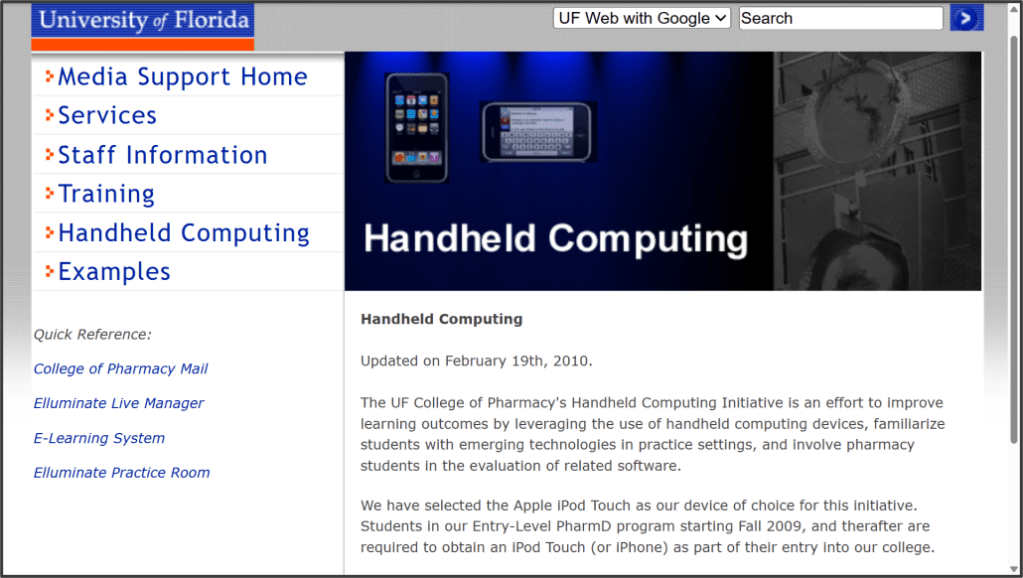

The UF College of Nursing’s strategic plan calls for curriculum innovation, and I’ve had the opportunity to both collaborate and lead in this area. For example, I directed the College of Pharmacy’s Handheld Computing Initiative in 2009.

As shown in the screenshot below, our objectives were to improve learning outcomes by leveraging mobile devices, familiarize students with emerging technologies in practical settings, and engage pharmacy students in the evaluation of relevant software.

We were acutely aware that this device requirement represented a substantial cost for our students; and we worked proactively and collaboratively with interested faculty to ensure these devices would be utilized. To address faculty skepticism, I tasked one of my talented instructional designers with researching how mobile devices could enhance learning. The document below was one of the many resources we provided faculty to contextualize this initiative.

We also collaborated with central campus IT staff to leverage Apple’s iTunesU service to ensure all of the college’s instructional video content could be made available on our students’ “iDevices”. We provided training to both faculty and students on various ways these devices could enhance learning. One example follows below. Typos have been preserved to ensure authenticity. 🫠

At the end of our first year of this initiative, the majority of students indicated the use of mobile technology was “extremely valuable” to their learning.

My more recent innovative work involved collaborating with SF College’s Disabilities Resources Center to use AI to make instructional content more accessible. We co-created and facilitated a campus-wide workshop titled Using AI for Improved Accessibility and Instruction. A video from this workshop follows. For context: I uploaded a photo of my classroom into ChatGPT and asked it to describe the image. In this video, you’ll hear the voice of screen reading software as it describes the content of the page.

I was pleasantly surprised that ChatGPT noticed the “haphazard” arrangement of the furniture. I might not have thought to include that description. We tend to think of visually impaired learners as sighted or blind. However, most visually impaired people have some degree of vision. A student with low vision might benefit from knowing that the chairs are arranged randomly as they enter the classroom.

Together, these projects reflect an ongoing commitment: using technology not for its novelty, but to remove barriers to learning and provide students and faculty with practical, evidence-based tools.

Between Chapters: A Year of Academic Reflection

This past year has provided me an opportunity to both upskill and more deeply explore Artificial Intelligence (AI) tools and services. I’ve worked with educational, commercial and non-profit clients centered around media development and accessibility. When clients share their locations, I enjoy naming project folders after them. As you can see in the image below, I’ve worked with clients from exotic places like Kosovo and Des Moines. 😄

Nursing within the Context of AI

Setting the Stage

In a recent keynote, OpenAI CEO Sam Altman introduced ChatGPT 5.0. Notably, this version achieved the highest score on the company’s internal HealthBench metric, described as “an evaluation for AI systems and human health.” The healthcare segment of the presentation was both the longest and the only one personally moderated by Altman himself — signaling that OpenAI may be positioning one or more of its products as healthcare services. The relevant segment begins at 35:10.

The demo raised difficult questions. In one example, a patient named Carolina processed alarming health news almost entirely with ChatGPT. For three hours, no one was available to speak with her in person. While the AI provided analysis, what struck me most was the absence of a healthcare provider or patient advocate who could have offered empathy and comfort in that moment.

We should not offload empathy and caregiving to AI.

Of lesser concern, the closed captions in the livestream lagged noticeably. That made sense in a live broadcast, but the recording released later still hadn’t been corrected. For a company presenting itself as a potential healthcare partner, the lack of attention to accessibility was surprising.

AI tools will undoubtedly play a growing role in healthcare, but their integration must be guided by clear boundaries. In nursing education especially, the challenge will be teaching students not just to use AI as a resource, but also to understand its limitations and to preserve the irreplaceable human elements of care.

How I (try to) Keep Up

These past few years have brought a flood of new AI services and tools. I use AI tools in my daily professional life; and I have a personal interest in AI … and, it still feels like a struggle to remain current. Here are some of the resources I use:

For general education trends, I read the Chronicle of Higher Education, Faculty Focus, and similar publications. In the past, I’ve attended webinars, joined listservs and attended the occasional conference. With regards to technology trends, I follow:

- Joanna Stern: Tech Reporter, Wall Street Journal

- Matt Wolfe: AI News Reporter and Reviewer

- Nilay Patel: Editor in Chief, The Verge

- WaveForm: Weekly audio podcast on new tech

Looking Ahead

Just last week, Google introduced a new video-generation tool embedded in its Notebook LM service. Originally limited to producing podcasts with AI-generated voices, the tool now creates slides with text, simple images, and synchronized narration.

While technically impressive, the output falls short pedagogically. In my test run, the slides sometimes displayed dense blocks of text simultaneously with an AI narrator voicing different lengthy content—a textbook case of cognitive overload. Progressive disclosure of bullet points or pairing visuals with narration would have been more effective. That said, the speed of development suggests that even these clunky outputs may soon evolve into highly polished tools. An example video follows. The audio begins at :19 seconds.

Looking ahead, the UF College of Nursing’s strategic plan emphasizes health equity. As AI tools become embedded in healthcare and education, this commitment should guide decisions about which platforms to adopt. One example is Latimer.ai, a large language model trained with diverse histories and inclusive voices. By design, it aims to reduce biases common in frontier chatbots.

Like any new tool, Latimer requires careful evaluation — especially regarding privacy. Yet it also presents an opportunity for action research: how might inclusive AI affect students’ sense of belonging and how they inform patient education and communication?

In 2023, I attended an AI conference hosted by Tennessee State University, where TSU announced institutional Latimer.ai licenses for interested HBCUs. That experience underscored how higher education can lead in shaping inclusive uses of AI. A partnership between UF Nursing and institutions with similar commitments could yield shared datasets, practical guidelines, and faculty development models that center equity and privacy.

Thank you for taking the time to review my work. I look forward to learning more about the college’s future plans and initiatives.